![]()

What is psychosurgery ?

Holes in the skull: ancient psychosurgery ?

The early pioneers

The history of lobotomy

Lobotomy's Hall of Fame

Modern psychosurgery

Stereotactic psychosurgery

Psychosurgery today

Resources in the Internet

![]()

For many people, psychosurgery is an ominous word. It has

the power to recall the nightmare of lobotomy,

the ill-fated brain operation invented by a Portuguese physician, Dr. Egas Moniz,

which maimed for life thousands upon thousands of mentally disturbed persons in the 40s. Included among its victims,

there were many

well-known personalities, such as

the sister of American President John Kennedy and the Hollywood actress Frances Farmer.

For many people, psychosurgery is an ominous word. It has

the power to recall the nightmare of lobotomy,

the ill-fated brain operation invented by a Portuguese physician, Dr. Egas Moniz,

which maimed for life thousands upon thousands of mentally disturbed persons in the 40s. Included among its victims,

there were many

well-known personalities, such as

the sister of American President John Kennedy and the Hollywood actress Frances Farmer.

Many books, plays and motion pictures have dealt with this subject, oftentimes portraying psychosurgery as a darkly evil and authoritarian way to control undesirable behavior, such as in "Clockwork Orange", by Anthony Burgess (the picture above shows actor Malcom McDowell being subjected to a brain-control session), or the Oscar-studded "One Flew Over the Cuckoo's Nest", with actor Jack Nicholson.

But

what is fact and what is fiction ?

But

what is fact and what is fiction ?

How psychosurgery evolved from the crude skull-drilling operations, used by shamans and physicians since Neolithic times to ward off the demons of brain and mind diseases, into a modern procedure to alter human behavior ?

Is psychosurgery being used today ? For what purpose ?

Psychosurgery is the scientific treatment of mental disorders by means of brain surgery.

It may sound absurd that the destruction of an area of the brain, the most delicate and complex of all organs, could lead to an improvement of a mental process. But this notion is neither new nor absurd in medicine. Just think what happens when another organ or tissue, such as a gland, gets diseased and threatens the balance and survival of the whole organism. Many times the only solution is to remove it permanently and eliminate the source of the pathology.

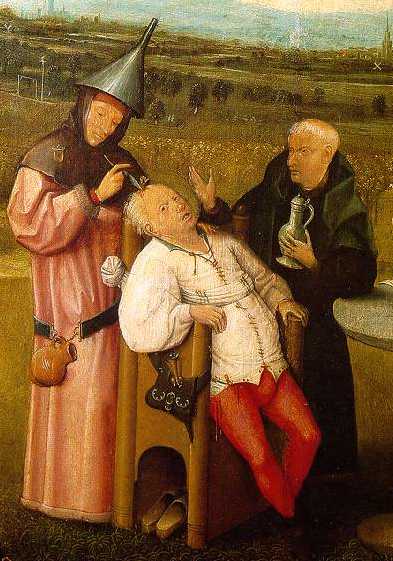

The historical antecedents of modern psychosurgery are lost in the most distant past. Already in the Neolithic times, 40,000 years ago, man performed skull surgery, as archeological findings have unearthed thousands of skulls all over the world, with holes bored on them. This surgery, called trepanning, was probably carried out to "liberate" demons and bad spirits which the ancient doctors believed were responsible for madness and brain disease.

In the Medieval times, there was a period where bogus operations performed by quack doctors, to extract the so-called "stone of madness", which they wanted people to believe was the source of mental disease.

However, it was only in the last years of the 19th century that rational approaches to psychosurgery were first tried. A Swiss surgeon named Burkhardt, performed in 1894 an operation to destroy selectively the frontal lobes of several patients, which he thought would be able to control psychotic symptoms. The knowledge that this part of the brain was involved in emotions was already known from clinical cases where they were destroyed by accidents or tumors, such as the famous case of Phineas Gage, or by animal experiments. Furthermore, the advent of anesthesia and asepsis, and the technical progress in conventional neurosurgery brought by pioneers such as Sir Victor Horsley, in the United Kingdom, and Harvey Cushing, in the USA; made possible surgical approaches to the brain which were not possible before.

The first consistent technique for psychosurgery was developed by Portuguese neurologist Dr. Antônio Egas Moniz, and performed for the first time in 1935, with his colleague, Almeida Lima. Moniz based his operation on the finding, made a few years before, that certain neurotic symptoms induced in chimpanzees could be decreased by cutting the nerve fibers connecting the prefrontal cortex to the rest of the brain. He then developed a technique, called leucotomy, or lobotomy, which consisted in severing fiber tracts between the thalamus and the frontal lobes, using a special knife, which he called a leucotome.

His results were considered so good, that lobotomy started to be used in several countries as a radical, last-ditch attempt at reducing psychosis and severe depression or violent behavior in patients who could not be treated with any other means (at the time, there were not many: insulin-induced shock and electroconvulsive shock were also in their beginning stages, and drugs were still not available). Thus, lobotomy was used mostly in institutionalized patients who showed also chronic agitation or distress and obsessive-impulsive behavior. Moniz was awarded the Nobel in 1949 for his discovery.

Two American surgeons, Walter Freeman and Watts, adopted enthusiastically Moniz' s procedure, and improved it. They developed a quick and easy surgical procedure called "trans-orbital leucotomy", which could be done in a few minutes under local anesthesia in a medical office. It consisted in the insertion, with the slight blow of a hammer, of an ice pick instrument through the roof of the orbits, and a rapid sideway movement to severe the fibers. Freeman operated, lectured and taught extensively in the United States, popularizing leucotomy as a tool to control undesirable behavior across the nation's insane asylums, hospitals and psychiatric clinics.

Thus, in the 40s and 50s, more than 50,000 persons were subjected to lobotomy all over the world, based on a very scanty and flimsy (and most say unwarranted) evidence for its scientific basis. Soon it became apparent that, although lobotomy was able to curtain severely agitated and violent behavior, becalming psychotic patients; there were many undesirable effects. Prefrontal lobotomy produced "zombies", persons without emotions, apathic to everything, and reduced drive and initiative. They also lost several important higher mental functions, such as socially adequate behavior and the capability to plan actions.

In many instances, lobotomy was widely abused as a last-resort tool, as Egas Moniz wanted, and it was carried out in problem children, rebel adolescents and political opponents.

With the appearance of effective drugs against anxiety, depression and psychoses, in the 50s, and with the evidence of its widespread abuse and collateral effects, lobotomy and other forms of leucotomy were condoned and abandoned in that decade, and are no longer performed.

But this was not the end of psychosurgery. With the advance of the minimally-invasive surgical

techniques, such as functional stereotactic

neurosurgery, physicians were able

to destroy with high precision much smaller areas of the brain involved in emotional control. Scientific knowledge

about the system that controlled behavior was also becoming available. These small lesions have virtually no effect

on other intellectual or emotional spheres, and are generally very effective in controlling violent behavior caused

by intracranial tumors or an irritative or epileptic focus in the "emotional" part of the brain. Untreatable

severe depression and anxiety, or chronic pain caused by damage to the nervous system or terminal cancer, can benefit

from stereotactic cingulectomy (the lesion of the cingular cortex) or amygalectomy (the lesion of the amygaloid

bodies).

But this was not the end of psychosurgery. With the advance of the minimally-invasive surgical

techniques, such as functional stereotactic

neurosurgery, physicians were able

to destroy with high precision much smaller areas of the brain involved in emotional control. Scientific knowledge

about the system that controlled behavior was also becoming available. These small lesions have virtually no effect

on other intellectual or emotional spheres, and are generally very effective in controlling violent behavior caused

by intracranial tumors or an irritative or epileptic focus in the "emotional" part of the brain. Untreatable

severe depression and anxiety, or chronic pain caused by damage to the nervous system or terminal cancer, can benefit

from stereotactic cingulectomy (the lesion of the cingular cortex) or amygalectomy (the lesion of the amygaloid

bodies).

The development of radiosurgery by a Swedish neurosurgeon, Dr. Lars Leksell, in the 70s, now allows physicians to remove tiny amounts of brain tissue without actually opening the skull. Using directed beams of high-energy radiation produced by a linear accelerator, a nuclear pile or external sources of radioactive cobalt, as well as computers and advanced neural imaging techniques (computed tomography), surgeons are now able to pinpoint with great accuracy areas, nuclei or fibers inside the brain. However, fewer than 200 surgeries of this type were performed every year in the United States, because its indication is highly selective.

|