| Our

Ancient Laughing Brain

Courtesy of Cerebrum |

Imitation or Instinct?

Photo by Eibl-Eibesfeldt (2) |

In his classic cross-cultural studies, Irenäus Eibl-Eibesfeldt, father of human ethology (the study of the biological basis of behavior), documented laughter’s universality. To do so, he devised a curious and effective method of filming people in natural settings without affecting their behavior. He attached an optical prism to the camera’s lens so that he could photograph people who were at right angles to the direction in which he pointed it, catching them unaware. With this technique he filmed the social interactions and facial expressions of thousands of individuals: Brazilian Indians, African tribesmen, Greek fishermen, British businessmen. In every culture that he investigated, all people laughed: in surprise, wonderment, embarrassment, and discomfort—not necessarily, or even frequently, in amusement. |

| Do we learn to

laugh? Or is laughter innate in human beings, an ability hardwired into

our brains? That laughter is present in all cultures, even tribes wholly

isolated from all others, is not firm evidence that it is innate. Even

an infant who laughs could be imitating a parent’s laughter.

I believe, however, the evidence points to an innate, preprogrammed basis for laughter. Studies of congenitally blind, deaf, and dumb children, for example, proved that they could smile and laugh when tickled or caressed, even though they were unable to imitate other people. |

Blind and deaf child victims of talidomide Photo by Eibl-Eibesfeldt (2) |

If laughter is innate, there might be evidence

for it in the evolutionary record. We cannot know whether primitive Homo

sapiens—or our predecessor hominids on the African plain—laughed as we

do, but by observing the primates closest to humans we see that laughter

is not unique to ourselves.

| If we are but one among many social species, after all, why should we have a monopoly on laughter as a social tool? |

|

Scientists have known for a century that

the great apes, such as chimpanzees, display something similar to human

laughter. They open their mouths wide, expose their teeth, retract the

corners of their lips, and emit loud and repetitive vocalizations, much

like ha! ha! ha! Chimps laugh in situations that tend to evoke human laughter,

for example, when playing with one another or with humans, or when tickled.

|

Laughter may even have evolved long before

primates appeared on the scene. When tickled, rats emit vocalizations that

could be interpreted as laughter.3 Neurobiologist Jaak Panksepp found that

juvenile rats emit short, high-frequency, ultrasonic vocalizations during

rough-and-tumble play.4 They “laugh” more often than older rats do, which

Panksepp sees as consonant with the observation that human children are

more ticklish than adults.

Animals may not have a sense of humor,

which I will argue is uniquely human, but they do have a sense of fun.

Panksepp suggests that rats and primates, especially juveniles, use laughter to distinguish playful from threatening physical interactions. We watch puppies tumble over each other, snarl, and pretend to bite or give chase. To us, they clearly are having fun with this make-believe fighting, but subtle modifications of behavior, including vocalizations, signal to their partners that the fight is not serious. A puppy’s inability to signal (because of a damaged brain or having been raised in isolation) leads to serious fighting.

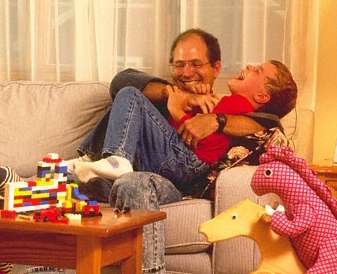

Children of all ages—and, in many cultures, fathers and sons—also engage in rough-and-tumble play, with pretend punching and boxing and much accompanying laughter. Perhaps this is when we learn how to use laughter to indicate that aggressive play is just in fun. As a consequence, positive emotional bonds form among siblings and between parents and children.

Not coincidentally, teeth baring in primate displays of aggression and in laughter are similar. Small variations in the position of the lips and in the accompanying sounds differentiate the two displays. Is this a clue to a common neural and evolutionary origin of laughter and aggression? Laughing in potentially aggressive or competitive situations disarms our social companions. On the verge of becoming our adversaries, they pick up from our laughter that the situation is not threatening.

In English, play refers not only to sport

or children’s games but to acting a role on stage or in a movie. Play is

a multifunctional concept applying to situations that involve laughter

and make-believe. I hypothesize that human laughter has evolved culturally

into a kind of “displaced behavior,” the term used by ethologists for animal

behaviors that appear to be out of context—for example, birds that pretend

to peck things on the ground when they are threatened by another bird.

Laughter may have its biological origin in warding off aggression and offsetting

nervousness in the face of a threatening situation, but the amazing social

capacity of Homo sapiens has led to its use as a general tool in many situations,

as well as a pleasurable behavior in its own right.

In many species with complex social structures,

play extends into adult life. For human beings, widely accepted forms of

play such as games and sports are essential for social cohesion. Have you

noticed how television sports commentators laugh and banter with each other?

Adult play and laughter are indissoluble. You do not usually see such behavior,

for example, with the commentators on economic news.